Ch. 10: The Arts and Crafts Movement

The Arts and Crafts movement was led by William Morris. It was a renaissance of book design, focusing on using a book as a limited-edition art object, and then influenced commercial production. This boomed in Europe during the last decades of the 19th century. The reaction against social, moral and artistic uncertainty of the Industrial Revolution called for individual expression and a mastery over materials and artistic expression. John Ruskin, an artist and writer, created the philosophy of the movement; he wanted to bring art and society back together by rejecting the mercantile economy and rejoining art and labor. Morris, influenced by his life in the beautiful English countryside, was an avid writer and reader, also dabbled in the arts, and upon building his “Red House” began to design his own interior decorations and furniture—which turned into a vocation for him. He continued to lead his business in a moral manner, careful not to exploit or distress his workers with his work.

I was impressed that people were able to take a step back during this booming time period to question whether the mass production process was morally right for workers, as well as giving justice to art and design. Unfortunately, I don’t think many people do that today as we are just as much a mass-production-driven society as ever—the world is manufacturing like never before, and many of the ideas of the Arts and Crafts movement are not remembered or even known by most workers, designers or company owners.

The question I wonder about is, in a time when money matters, is it sensible to take this kind of stance on production and mass goods? Or should one always look at art as a pure object and be constantly abhorred at how it is so used up and abused today?

Thursday, February 26, 2009

2/25 After Class

In class, we discussed the Industrial Revolution, which covered topics including the steam engine, advertising, wood type, the steam press, photography and its influence.

We divided into groups to talk about how we’d describe the era’s style. The steam engine had an effect because it replaced many workers’ jobs; its increase in production led to the need in advertising. Fat faces, or display letterforms, were made; wood type allowed these to be cheap, much larger, and decorative. Sans-serif fonts like Caslon were introduced, images were put into type forms; and Mergenthaler’s linotype machine (1886) cut out the jobs of compositors and allowed work to be done 25-30% faster. The camera obscura was a drawing aid for artists, and this allowed for the invention of photography—in 1826, the first photograph of nature was taken. In 1844, the first fully photographic book was published, though the photos had to be carved into wood to print over and over. Kodak cameras were developed, and photographs of important historical events were able to be recorded (like the freeing of the slaves, interviews, and the Civil War). In 1880, half tones were invented to print photos into the New York Daily Graphic.

The most useful part of this chapter was to see how far graphic design has developed; and as we know it today (at least from the marketing/advertising perspective), it has not been around for much longer than 200 years, which means it has much more development to go through (as everything does).

I am interested in seeing how in the later chapter we see more and more technologies cropping up faster to change the way advertising is used—like the internet.

We divided into groups to talk about how we’d describe the era’s style. The steam engine had an effect because it replaced many workers’ jobs; its increase in production led to the need in advertising. Fat faces, or display letterforms, were made; wood type allowed these to be cheap, much larger, and decorative. Sans-serif fonts like Caslon were introduced, images were put into type forms; and Mergenthaler’s linotype machine (1886) cut out the jobs of compositors and allowed work to be done 25-30% faster. The camera obscura was a drawing aid for artists, and this allowed for the invention of photography—in 1826, the first photograph of nature was taken. In 1844, the first fully photographic book was published, though the photos had to be carved into wood to print over and over. Kodak cameras were developed, and photographs of important historical events were able to be recorded (like the freeing of the slaves, interviews, and the Civil War). In 1880, half tones were invented to print photos into the New York Daily Graphic.

The most useful part of this chapter was to see how far graphic design has developed; and as we know it today (at least from the marketing/advertising perspective), it has not been around for much longer than 200 years, which means it has much more development to go through (as everything does).

I am interested in seeing how in the later chapter we see more and more technologies cropping up faster to change the way advertising is used—like the internet.

Ch. 9 Summary

Chapter 9 is all about the industrial revolution and its influence on typography and graphic design. It began with the invention of the steam engine in the 1780s by James Watt; this invention took over many peoples’ jobs and people would try to sabotage inventions like these time-saving machines for that reason—like Ottmar Mergenthaler’s linotype machine. Manufacturers began to require marketing for their products, and “fat faces” became popular as their thick type forms called attention. Photography was also developed during the revolution; first the camera obscura, then the use of chemical paper, then negatives. In 1844 “The Pencil of Nature” was the first book illustrated with photographs. Lithography and chromolithography became popular as realistic pictures could be portrayed, in color especially. And, for the first real time, children’s books and media were designed. The Victorian era saw an influx of magazines and papers, and likewise advertising agencies, as well as fancy typefaces, such as those by Cummings, that aren’t practical for today’s standards.

I was amazed by the rapid advancement that civilization made over the 1700s-1900s. The early history of typography moves so slowly, and though it is amazing to think of completely uncivilized people able to have these insights to develop something like a language, it is more amazing to see civilized people and the technological breakthroughs their imaginative minds can come to.

Children’s books became available during the Victorian era; when did women’s publications become a common thing? Was it very long before children’s media, or about the same time?

I was amazed by the rapid advancement that civilization made over the 1700s-1900s. The early history of typography moves so slowly, and though it is amazing to think of completely uncivilized people able to have these insights to develop something like a language, it is more amazing to see civilized people and the technological breakthroughs their imaginative minds can come to.

Children’s books became available during the Victorian era; when did women’s publications become a common thing? Was it very long before children’s media, or about the same time?

Saturday, February 21, 2009

Weekly Image

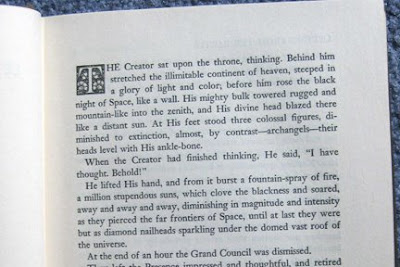

This is an image of the first page of Mark Twain’s “Letters from the Earth” edited by Bernard Devoto, ©1962 The Mark Twain Co. and published by Harper & Row, NY.

The book is a novel by Mark Twain that I checked out of the library to read. It was written to entertain and also to make people think more deeply about God and his creation of the world. This page is the first page of the novel.

What caught my eye first on the page is the capital T and the ornate box that it is enclosed in; it is reminiscent of Geoffrey Tory’s criblé and floral initials that he created in the 1500s. It has floral design as well as the criblé markings (the small dots) in the empty spaces. It is smaller and uncolored, though, while I think Tory’s initials were larger and usually in color.

I also looked at the typeface used for the book: Linotype Janson. When I looked it up, I found that it is based on a 17th century Hungarian old-style serif typeface that looks similar to many of the old-style typefaces we have been looking at in class. It uses ligatures for certain letter combinations, such as ‘fl’, which I usually don’t notice in most books I read—though perhaps I just pay closer attention now that I am more aware of them from the class!

Also, we obviously see the “modern” clean and simple design of the book with its empty and wide margins around the text.

I like the fusion of the old and new that this book presents; with the subject being religious in nature, I think it is fitting to have an old-style typeface as well as ornate initial on the page. The modern book design, though, allows the book to fit into modern-day standards and norms that we are used to so that it is still easy to read.

Sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Janson

Thursday, February 19, 2009

After Class 2/18

Chapter 8: An Epoch of Typographic Genius – Including the Romain du Roi typeface, Rococo period, Old Style/Transitional/Modern type, and influential typographers

French King Louis XIV commissioned the Romain do Roi to be created for his Imprimerie Royale printers; the typeface had increased contrast between thick and thin strokes, sharp horizontal serifs and balance; it was illegal for anyone besides the King’s people to use it. It was the first of the “transitional roman” types; later, Baskerville’s transitional typeface, which he printed on woven paper for a smoother finish, was seen as a “transitional” type too. Caslon’s type looked more hand-written and “friendly to the eye” and was considered an “Old Style” typeface with its bracketed serifs and uniform thickness. Didot and Bodoni’s typefaces were seen as more mechanic and considered “modern” because of their narrower and more geometric letters with a vertical axis. The Rococo period featured fanciful French art and lasted from 1720-1770. It was floral, intricate, asymmetrical, and featured many scrolls and curves. Also during this epoch of genius we saw the start of information graphics, like charts, as well as le Jeune pioneering the standardization of types and type faces.

The most useful parts of the chapter to me were analyzing the different typefaces and the differences among them, which made me look more closely at typefaces in general, as well as able to see the differences in typefaces used today. It will make me think and look more closely at the typefaces I use in the future.

Were the promiscuous/entertaining texts back then used by the rich, who also spent their money on the religious texts, or were they used by the poorer people?

French King Louis XIV commissioned the Romain do Roi to be created for his Imprimerie Royale printers; the typeface had increased contrast between thick and thin strokes, sharp horizontal serifs and balance; it was illegal for anyone besides the King’s people to use it. It was the first of the “transitional roman” types; later, Baskerville’s transitional typeface, which he printed on woven paper for a smoother finish, was seen as a “transitional” type too. Caslon’s type looked more hand-written and “friendly to the eye” and was considered an “Old Style” typeface with its bracketed serifs and uniform thickness. Didot and Bodoni’s typefaces were seen as more mechanic and considered “modern” because of their narrower and more geometric letters with a vertical axis. The Rococo period featured fanciful French art and lasted from 1720-1770. It was floral, intricate, asymmetrical, and featured many scrolls and curves. Also during this epoch of genius we saw the start of information graphics, like charts, as well as le Jeune pioneering the standardization of types and type faces.

The most useful parts of the chapter to me were analyzing the different typefaces and the differences among them, which made me look more closely at typefaces in general, as well as able to see the differences in typefaces used today. It will make me think and look more closely at the typefaces I use in the future.

Were the promiscuous/entertaining texts back then used by the rich, who also spent their money on the religious texts, or were they used by the poorer people?

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Chapter 8

Chapter 8: An Epoch of Typographic Genius

This chapter delved into the time of mastery over typography. This all began with French King Louis XIV and his Imprimerie Royale, his royal printing office. Under his commission in 1692, mathematician Jaugeon created the Romain du Roi typeface, which had increased contrast between thick and thin, sharp horizontal serifs, and more balance. It became the forerunner of the “transitional Roman type” category. The Rococo period followed with the influence of fancy French art: floral, intricate, asymmetrical decoration with scrolls and curves, classical and oriental art, and colors that ranged from pastels to ivory and gold were in. In 1737, Fournier le Jeune pioneered standards of type by publishing a table of proportions. He made many other contributions, including publishing manuals of typography. Over the years, engravers became more skilled and began to produce books by hand-engraving both illustrations and text. In 1722, William Caslon created his Caslon Old Style; Baskerville was an all-around book designer who first came out with a shiny page of type, using an unknown method to achieve the luster. Bodoni’s page layouts, which lacked the extravagance of former styles, introduced the simplistic modern layouts that we know today.

I think I was most excited in this chapter to see names that I recognize, especially type faces (Caslon, Bodoni, etc.). I was also happy to see the influences that are more prevalent today, and the simplistic book designs that we all know.

Why was the Rococo period called the “Rococo” period? Where did that name come from?

This chapter delved into the time of mastery over typography. This all began with French King Louis XIV and his Imprimerie Royale, his royal printing office. Under his commission in 1692, mathematician Jaugeon created the Romain du Roi typeface, which had increased contrast between thick and thin, sharp horizontal serifs, and more balance. It became the forerunner of the “transitional Roman type” category. The Rococo period followed with the influence of fancy French art: floral, intricate, asymmetrical decoration with scrolls and curves, classical and oriental art, and colors that ranged from pastels to ivory and gold were in. In 1737, Fournier le Jeune pioneered standards of type by publishing a table of proportions. He made many other contributions, including publishing manuals of typography. Over the years, engravers became more skilled and began to produce books by hand-engraving both illustrations and text. In 1722, William Caslon created his Caslon Old Style; Baskerville was an all-around book designer who first came out with a shiny page of type, using an unknown method to achieve the luster. Bodoni’s page layouts, which lacked the extravagance of former styles, introduced the simplistic modern layouts that we know today.

I think I was most excited in this chapter to see names that I recognize, especially type faces (Caslon, Bodoni, etc.). I was also happy to see the influences that are more prevalent today, and the simplistic book designs that we all know.

Why was the Rococo period called the “Rococo” period? Where did that name come from?

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

After Class 2/16

1. Name of graphic style (or topic) studied this session:

In class 2/16, we studied Gutenberg’s influence on typography and how it affected societies; broadsides; Albrecht Durer; Martin Luther; Venice and the Renaissance there; Nicolas Jenson; Ratdolt, Manutius and Tory—all Renaissance men of their times.

2. Describe specific qualities of this style (or if it’s a topic-highlights of that topic) that will help you identify it in the future.

Typography affected society by reducing the costs of text which led to widespread literacy (even in less fortunate people); spreading ideas and sciences; stabilizing languages; individualism; and more. Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses were proliferated around Europe thanks to Gutenberg’s advances of printing, which led to the Reformation of Christian faith. On a smaller scale, broadsides, which were single-leaf pages printed on one side, evolved into posters, advertisements and newspapers. Albrecht Durer, who was the master behind “The Apocalypse” perfected Roman capitals with his use of geometry and also brought the Italian Renaissance to Germany after studying there. Ratdolt was a Renaissance man who got out scientific ideas, such as the solar/lunar eclipse, into print. He also had the first complete title page, the first type specimen sheet, and the first dye-cut in a published book. Manutius was also a Renaissance man who started the printing of pocket books; helped develop italics, printed the works of many great thinkers; and had the first logo. Finally, Geoffrey Tory, the greatest Renaissance man of all, was proficient in twelve different areas of study; he greatly influenced the French alphabet and grammar with the introduction of the cedilla, apostrophe and accent. His three-volume work, Champ Fleury, influenced his whole generation of print makers.

3. What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today?

I liked looking at the progression of the “Renaissance Man” especially in Italy. The men who worked in earlier times seem now not to have discovered anything so profound compared to the men who succeeded them, but without those first accomplishments, their followers may never have reached the conclusions that they did. Even the smallest achievements back then were and still are a great impact on humanity.

Question: When the Renaissance time period was reached, were books and printed materials still used mainly for religious/scientific purposes, or were they being used yet for other areas or even for entertainment?

In class 2/16, we studied Gutenberg’s influence on typography and how it affected societies; broadsides; Albrecht Durer; Martin Luther; Venice and the Renaissance there; Nicolas Jenson; Ratdolt, Manutius and Tory—all Renaissance men of their times.

2. Describe specific qualities of this style (or if it’s a topic-highlights of that topic) that will help you identify it in the future.

Typography affected society by reducing the costs of text which led to widespread literacy (even in less fortunate people); spreading ideas and sciences; stabilizing languages; individualism; and more. Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses were proliferated around Europe thanks to Gutenberg’s advances of printing, which led to the Reformation of Christian faith. On a smaller scale, broadsides, which were single-leaf pages printed on one side, evolved into posters, advertisements and newspapers. Albrecht Durer, who was the master behind “The Apocalypse” perfected Roman capitals with his use of geometry and also brought the Italian Renaissance to Germany after studying there. Ratdolt was a Renaissance man who got out scientific ideas, such as the solar/lunar eclipse, into print. He also had the first complete title page, the first type specimen sheet, and the first dye-cut in a published book. Manutius was also a Renaissance man who started the printing of pocket books; helped develop italics, printed the works of many great thinkers; and had the first logo. Finally, Geoffrey Tory, the greatest Renaissance man of all, was proficient in twelve different areas of study; he greatly influenced the French alphabet and grammar with the introduction of the cedilla, apostrophe and accent. His three-volume work, Champ Fleury, influenced his whole generation of print makers.

3. What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today?

I liked looking at the progression of the “Renaissance Man” especially in Italy. The men who worked in earlier times seem now not to have discovered anything so profound compared to the men who succeeded them, but without those first accomplishments, their followers may never have reached the conclusions that they did. Even the smallest achievements back then were and still are a great impact on humanity.

Question: When the Renaissance time period was reached, were books and printed materials still used mainly for religious/scientific purposes, or were they being used yet for other areas or even for entertainment?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)