Ch. 10: The Arts and Crafts Movement

The Arts and Crafts movement was led by William Morris. It was a renaissance of book design, focusing on using a book as a limited-edition art object, and then influenced commercial production. This boomed in Europe during the last decades of the 19th century. The reaction against social, moral and artistic uncertainty of the Industrial Revolution called for individual expression and a mastery over materials and artistic expression. John Ruskin, an artist and writer, created the philosophy of the movement; he wanted to bring art and society back together by rejecting the mercantile economy and rejoining art and labor. Morris, influenced by his life in the beautiful English countryside, was an avid writer and reader, also dabbled in the arts, and upon building his “Red House” began to design his own interior decorations and furniture—which turned into a vocation for him. He continued to lead his business in a moral manner, careful not to exploit or distress his workers with his work.

I was impressed that people were able to take a step back during this booming time period to question whether the mass production process was morally right for workers, as well as giving justice to art and design. Unfortunately, I don’t think many people do that today as we are just as much a mass-production-driven society as ever—the world is manufacturing like never before, and many of the ideas of the Arts and Crafts movement are not remembered or even known by most workers, designers or company owners.

The question I wonder about is, in a time when money matters, is it sensible to take this kind of stance on production and mass goods? Or should one always look at art as a pure object and be constantly abhorred at how it is so used up and abused today?

Thursday, February 26, 2009

2/25 After Class

In class, we discussed the Industrial Revolution, which covered topics including the steam engine, advertising, wood type, the steam press, photography and its influence.

We divided into groups to talk about how we’d describe the era’s style. The steam engine had an effect because it replaced many workers’ jobs; its increase in production led to the need in advertising. Fat faces, or display letterforms, were made; wood type allowed these to be cheap, much larger, and decorative. Sans-serif fonts like Caslon were introduced, images were put into type forms; and Mergenthaler’s linotype machine (1886) cut out the jobs of compositors and allowed work to be done 25-30% faster. The camera obscura was a drawing aid for artists, and this allowed for the invention of photography—in 1826, the first photograph of nature was taken. In 1844, the first fully photographic book was published, though the photos had to be carved into wood to print over and over. Kodak cameras were developed, and photographs of important historical events were able to be recorded (like the freeing of the slaves, interviews, and the Civil War). In 1880, half tones were invented to print photos into the New York Daily Graphic.

The most useful part of this chapter was to see how far graphic design has developed; and as we know it today (at least from the marketing/advertising perspective), it has not been around for much longer than 200 years, which means it has much more development to go through (as everything does).

I am interested in seeing how in the later chapter we see more and more technologies cropping up faster to change the way advertising is used—like the internet.

We divided into groups to talk about how we’d describe the era’s style. The steam engine had an effect because it replaced many workers’ jobs; its increase in production led to the need in advertising. Fat faces, or display letterforms, were made; wood type allowed these to be cheap, much larger, and decorative. Sans-serif fonts like Caslon were introduced, images were put into type forms; and Mergenthaler’s linotype machine (1886) cut out the jobs of compositors and allowed work to be done 25-30% faster. The camera obscura was a drawing aid for artists, and this allowed for the invention of photography—in 1826, the first photograph of nature was taken. In 1844, the first fully photographic book was published, though the photos had to be carved into wood to print over and over. Kodak cameras were developed, and photographs of important historical events were able to be recorded (like the freeing of the slaves, interviews, and the Civil War). In 1880, half tones were invented to print photos into the New York Daily Graphic.

The most useful part of this chapter was to see how far graphic design has developed; and as we know it today (at least from the marketing/advertising perspective), it has not been around for much longer than 200 years, which means it has much more development to go through (as everything does).

I am interested in seeing how in the later chapter we see more and more technologies cropping up faster to change the way advertising is used—like the internet.

Ch. 9 Summary

Chapter 9 is all about the industrial revolution and its influence on typography and graphic design. It began with the invention of the steam engine in the 1780s by James Watt; this invention took over many peoples’ jobs and people would try to sabotage inventions like these time-saving machines for that reason—like Ottmar Mergenthaler’s linotype machine. Manufacturers began to require marketing for their products, and “fat faces” became popular as their thick type forms called attention. Photography was also developed during the revolution; first the camera obscura, then the use of chemical paper, then negatives. In 1844 “The Pencil of Nature” was the first book illustrated with photographs. Lithography and chromolithography became popular as realistic pictures could be portrayed, in color especially. And, for the first real time, children’s books and media were designed. The Victorian era saw an influx of magazines and papers, and likewise advertising agencies, as well as fancy typefaces, such as those by Cummings, that aren’t practical for today’s standards.

I was amazed by the rapid advancement that civilization made over the 1700s-1900s. The early history of typography moves so slowly, and though it is amazing to think of completely uncivilized people able to have these insights to develop something like a language, it is more amazing to see civilized people and the technological breakthroughs their imaginative minds can come to.

Children’s books became available during the Victorian era; when did women’s publications become a common thing? Was it very long before children’s media, or about the same time?

I was amazed by the rapid advancement that civilization made over the 1700s-1900s. The early history of typography moves so slowly, and though it is amazing to think of completely uncivilized people able to have these insights to develop something like a language, it is more amazing to see civilized people and the technological breakthroughs their imaginative minds can come to.

Children’s books became available during the Victorian era; when did women’s publications become a common thing? Was it very long before children’s media, or about the same time?

Saturday, February 21, 2009

Weekly Image

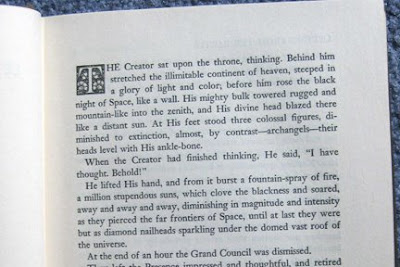

This is an image of the first page of Mark Twain’s “Letters from the Earth” edited by Bernard Devoto, ©1962 The Mark Twain Co. and published by Harper & Row, NY.

The book is a novel by Mark Twain that I checked out of the library to read. It was written to entertain and also to make people think more deeply about God and his creation of the world. This page is the first page of the novel.

What caught my eye first on the page is the capital T and the ornate box that it is enclosed in; it is reminiscent of Geoffrey Tory’s criblé and floral initials that he created in the 1500s. It has floral design as well as the criblé markings (the small dots) in the empty spaces. It is smaller and uncolored, though, while I think Tory’s initials were larger and usually in color.

I also looked at the typeface used for the book: Linotype Janson. When I looked it up, I found that it is based on a 17th century Hungarian old-style serif typeface that looks similar to many of the old-style typefaces we have been looking at in class. It uses ligatures for certain letter combinations, such as ‘fl’, which I usually don’t notice in most books I read—though perhaps I just pay closer attention now that I am more aware of them from the class!

Also, we obviously see the “modern” clean and simple design of the book with its empty and wide margins around the text.

I like the fusion of the old and new that this book presents; with the subject being religious in nature, I think it is fitting to have an old-style typeface as well as ornate initial on the page. The modern book design, though, allows the book to fit into modern-day standards and norms that we are used to so that it is still easy to read.

Sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Janson

Thursday, February 19, 2009

After Class 2/18

Chapter 8: An Epoch of Typographic Genius – Including the Romain du Roi typeface, Rococo period, Old Style/Transitional/Modern type, and influential typographers

French King Louis XIV commissioned the Romain do Roi to be created for his Imprimerie Royale printers; the typeface had increased contrast between thick and thin strokes, sharp horizontal serifs and balance; it was illegal for anyone besides the King’s people to use it. It was the first of the “transitional roman” types; later, Baskerville’s transitional typeface, which he printed on woven paper for a smoother finish, was seen as a “transitional” type too. Caslon’s type looked more hand-written and “friendly to the eye” and was considered an “Old Style” typeface with its bracketed serifs and uniform thickness. Didot and Bodoni’s typefaces were seen as more mechanic and considered “modern” because of their narrower and more geometric letters with a vertical axis. The Rococo period featured fanciful French art and lasted from 1720-1770. It was floral, intricate, asymmetrical, and featured many scrolls and curves. Also during this epoch of genius we saw the start of information graphics, like charts, as well as le Jeune pioneering the standardization of types and type faces.

The most useful parts of the chapter to me were analyzing the different typefaces and the differences among them, which made me look more closely at typefaces in general, as well as able to see the differences in typefaces used today. It will make me think and look more closely at the typefaces I use in the future.

Were the promiscuous/entertaining texts back then used by the rich, who also spent their money on the religious texts, or were they used by the poorer people?

French King Louis XIV commissioned the Romain do Roi to be created for his Imprimerie Royale printers; the typeface had increased contrast between thick and thin strokes, sharp horizontal serifs and balance; it was illegal for anyone besides the King’s people to use it. It was the first of the “transitional roman” types; later, Baskerville’s transitional typeface, which he printed on woven paper for a smoother finish, was seen as a “transitional” type too. Caslon’s type looked more hand-written and “friendly to the eye” and was considered an “Old Style” typeface with its bracketed serifs and uniform thickness. Didot and Bodoni’s typefaces were seen as more mechanic and considered “modern” because of their narrower and more geometric letters with a vertical axis. The Rococo period featured fanciful French art and lasted from 1720-1770. It was floral, intricate, asymmetrical, and featured many scrolls and curves. Also during this epoch of genius we saw the start of information graphics, like charts, as well as le Jeune pioneering the standardization of types and type faces.

The most useful parts of the chapter to me were analyzing the different typefaces and the differences among them, which made me look more closely at typefaces in general, as well as able to see the differences in typefaces used today. It will make me think and look more closely at the typefaces I use in the future.

Were the promiscuous/entertaining texts back then used by the rich, who also spent their money on the religious texts, or were they used by the poorer people?

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Chapter 8

Chapter 8: An Epoch of Typographic Genius

This chapter delved into the time of mastery over typography. This all began with French King Louis XIV and his Imprimerie Royale, his royal printing office. Under his commission in 1692, mathematician Jaugeon created the Romain du Roi typeface, which had increased contrast between thick and thin, sharp horizontal serifs, and more balance. It became the forerunner of the “transitional Roman type” category. The Rococo period followed with the influence of fancy French art: floral, intricate, asymmetrical decoration with scrolls and curves, classical and oriental art, and colors that ranged from pastels to ivory and gold were in. In 1737, Fournier le Jeune pioneered standards of type by publishing a table of proportions. He made many other contributions, including publishing manuals of typography. Over the years, engravers became more skilled and began to produce books by hand-engraving both illustrations and text. In 1722, William Caslon created his Caslon Old Style; Baskerville was an all-around book designer who first came out with a shiny page of type, using an unknown method to achieve the luster. Bodoni’s page layouts, which lacked the extravagance of former styles, introduced the simplistic modern layouts that we know today.

I think I was most excited in this chapter to see names that I recognize, especially type faces (Caslon, Bodoni, etc.). I was also happy to see the influences that are more prevalent today, and the simplistic book designs that we all know.

Why was the Rococo period called the “Rococo” period? Where did that name come from?

This chapter delved into the time of mastery over typography. This all began with French King Louis XIV and his Imprimerie Royale, his royal printing office. Under his commission in 1692, mathematician Jaugeon created the Romain du Roi typeface, which had increased contrast between thick and thin, sharp horizontal serifs, and more balance. It became the forerunner of the “transitional Roman type” category. The Rococo period followed with the influence of fancy French art: floral, intricate, asymmetrical decoration with scrolls and curves, classical and oriental art, and colors that ranged from pastels to ivory and gold were in. In 1737, Fournier le Jeune pioneered standards of type by publishing a table of proportions. He made many other contributions, including publishing manuals of typography. Over the years, engravers became more skilled and began to produce books by hand-engraving both illustrations and text. In 1722, William Caslon created his Caslon Old Style; Baskerville was an all-around book designer who first came out with a shiny page of type, using an unknown method to achieve the luster. Bodoni’s page layouts, which lacked the extravagance of former styles, introduced the simplistic modern layouts that we know today.

I think I was most excited in this chapter to see names that I recognize, especially type faces (Caslon, Bodoni, etc.). I was also happy to see the influences that are more prevalent today, and the simplistic book designs that we all know.

Why was the Rococo period called the “Rococo” period? Where did that name come from?

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

After Class 2/16

1. Name of graphic style (or topic) studied this session:

In class 2/16, we studied Gutenberg’s influence on typography and how it affected societies; broadsides; Albrecht Durer; Martin Luther; Venice and the Renaissance there; Nicolas Jenson; Ratdolt, Manutius and Tory—all Renaissance men of their times.

2. Describe specific qualities of this style (or if it’s a topic-highlights of that topic) that will help you identify it in the future.

Typography affected society by reducing the costs of text which led to widespread literacy (even in less fortunate people); spreading ideas and sciences; stabilizing languages; individualism; and more. Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses were proliferated around Europe thanks to Gutenberg’s advances of printing, which led to the Reformation of Christian faith. On a smaller scale, broadsides, which were single-leaf pages printed on one side, evolved into posters, advertisements and newspapers. Albrecht Durer, who was the master behind “The Apocalypse” perfected Roman capitals with his use of geometry and also brought the Italian Renaissance to Germany after studying there. Ratdolt was a Renaissance man who got out scientific ideas, such as the solar/lunar eclipse, into print. He also had the first complete title page, the first type specimen sheet, and the first dye-cut in a published book. Manutius was also a Renaissance man who started the printing of pocket books; helped develop italics, printed the works of many great thinkers; and had the first logo. Finally, Geoffrey Tory, the greatest Renaissance man of all, was proficient in twelve different areas of study; he greatly influenced the French alphabet and grammar with the introduction of the cedilla, apostrophe and accent. His three-volume work, Champ Fleury, influenced his whole generation of print makers.

3. What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today?

I liked looking at the progression of the “Renaissance Man” especially in Italy. The men who worked in earlier times seem now not to have discovered anything so profound compared to the men who succeeded them, but without those first accomplishments, their followers may never have reached the conclusions that they did. Even the smallest achievements back then were and still are a great impact on humanity.

Question: When the Renaissance time period was reached, were books and printed materials still used mainly for religious/scientific purposes, or were they being used yet for other areas or even for entertainment?

In class 2/16, we studied Gutenberg’s influence on typography and how it affected societies; broadsides; Albrecht Durer; Martin Luther; Venice and the Renaissance there; Nicolas Jenson; Ratdolt, Manutius and Tory—all Renaissance men of their times.

2. Describe specific qualities of this style (or if it’s a topic-highlights of that topic) that will help you identify it in the future.

Typography affected society by reducing the costs of text which led to widespread literacy (even in less fortunate people); spreading ideas and sciences; stabilizing languages; individualism; and more. Martin Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses were proliferated around Europe thanks to Gutenberg’s advances of printing, which led to the Reformation of Christian faith. On a smaller scale, broadsides, which were single-leaf pages printed on one side, evolved into posters, advertisements and newspapers. Albrecht Durer, who was the master behind “The Apocalypse” perfected Roman capitals with his use of geometry and also brought the Italian Renaissance to Germany after studying there. Ratdolt was a Renaissance man who got out scientific ideas, such as the solar/lunar eclipse, into print. He also had the first complete title page, the first type specimen sheet, and the first dye-cut in a published book. Manutius was also a Renaissance man who started the printing of pocket books; helped develop italics, printed the works of many great thinkers; and had the first logo. Finally, Geoffrey Tory, the greatest Renaissance man of all, was proficient in twelve different areas of study; he greatly influenced the French alphabet and grammar with the introduction of the cedilla, apostrophe and accent. His three-volume work, Champ Fleury, influenced his whole generation of print makers.

3. What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today?

I liked looking at the progression of the “Renaissance Man” especially in Italy. The men who worked in earlier times seem now not to have discovered anything so profound compared to the men who succeeded them, but without those first accomplishments, their followers may never have reached the conclusions that they did. Even the smallest achievements back then were and still are a great impact on humanity.

Question: When the Renaissance time period was reached, were books and printed materials still used mainly for religious/scientific purposes, or were they being used yet for other areas or even for entertainment?

Sunday, February 15, 2009

Chapters 6 & 7

Chapter 6: The German Illustrated Book

Incunabula means “cradle” in Latin; fittingly, 17th century writers used the term as a name for the books Gutenberg printed with his typography up until the end of the 15th century. Broadsides, or single pages that were printed on only one side, evolved into posters, advertisements and newspapers. Albrecht Durer also lent value to illustrated books through his 1498 edition of “The Apocalypse,” with 32 16”x12” pages including 15 woodcut illustrations on each right-hand page; and through his 1525 book, “A Course in the Art of Measurement with Compass and Ruler,” his first book.

It was most interesting to read about the flourishing of typography and the boom of printing shops to the point that there were too many for them all to have enough business. It’s sort of amusing because it now seems so elementary or basic, but then it was such a huge new technology, and it’s not until one analyzes the effects of easy printing that one can see why it was such a fantastic achievement.

///

Chapter 7: Renaissance of Graphic Design

This chapter focused on the renaissance of GD, or the transition of graphic design from the medieval times up to modern times. Venice was the powerhouse of typographic book design in Italy; de Spira had a 5-year monopoly on printing, and his innovative and attractive roman type (as well as France’s Jenson and his roman type) ushered in new fonts that closely resemble those we most use today. Floral decoration was used prominently on designs. Ratdolt made an impact as well with three-sided border illustrations, small geometric figures, and his best-selling “The Art of Dying.” The rapid boom of literacy allowed calligraphers to have new jobs of teaching newly literate people how to write when their old jobs were replaced by printing presses. Typographic printing had many effects, including reducing the cost of books/printed materials, spreading ideas and knowledge, stabilizing and unifying language, the helping literacy increase.

I really just enjoyed looking at the evolution of the many book pages pictured throughout this chapter; there were so many names and dates that it became more telling to look at the pictures and see the progress and changes in those than to read about them. It also was inspiring to see the different layouts and illustration styles that we rarely see today.

With the ability of typographic printing presses, how did illuminators keep up with the many sheets that were printed? I know many times woodblocks and carvings were used, but wouldn’t these wear down to the point that many copies of the carving be needed?

Incunabula means “cradle” in Latin; fittingly, 17th century writers used the term as a name for the books Gutenberg printed with his typography up until the end of the 15th century. Broadsides, or single pages that were printed on only one side, evolved into posters, advertisements and newspapers. Albrecht Durer also lent value to illustrated books through his 1498 edition of “The Apocalypse,” with 32 16”x12” pages including 15 woodcut illustrations on each right-hand page; and through his 1525 book, “A Course in the Art of Measurement with Compass and Ruler,” his first book.

It was most interesting to read about the flourishing of typography and the boom of printing shops to the point that there were too many for them all to have enough business. It’s sort of amusing because it now seems so elementary or basic, but then it was such a huge new technology, and it’s not until one analyzes the effects of easy printing that one can see why it was such a fantastic achievement.

///

Chapter 7: Renaissance of Graphic Design

This chapter focused on the renaissance of GD, or the transition of graphic design from the medieval times up to modern times. Venice was the powerhouse of typographic book design in Italy; de Spira had a 5-year monopoly on printing, and his innovative and attractive roman type (as well as France’s Jenson and his roman type) ushered in new fonts that closely resemble those we most use today. Floral decoration was used prominently on designs. Ratdolt made an impact as well with three-sided border illustrations, small geometric figures, and his best-selling “The Art of Dying.” The rapid boom of literacy allowed calligraphers to have new jobs of teaching newly literate people how to write when their old jobs were replaced by printing presses. Typographic printing had many effects, including reducing the cost of books/printed materials, spreading ideas and knowledge, stabilizing and unifying language, the helping literacy increase.

I really just enjoyed looking at the evolution of the many book pages pictured throughout this chapter; there were so many names and dates that it became more telling to look at the pictures and see the progress and changes in those than to read about them. It also was inspiring to see the different layouts and illustration styles that we rarely see today.

With the ability of typographic printing presses, how did illuminators keep up with the many sheets that were printed? I know many times woodblocks and carvings were used, but wouldn’t these wear down to the point that many copies of the carving be needed?

Weekly Image

Pictured above is an inside page for a flyer promoting “Ms. Coffmansen’s Portfolio Finishing School for Good Girls and Boys.” I picked up the flyer from the Eisner Museum in Milwaukee.

Pictured above is an inside page for a flyer promoting “Ms. Coffmansen’s Portfolio Finishing School for Good Girls and Boys.” I picked up the flyer from the Eisner Museum in Milwaukee.The function of the page is to promote the school and describe how students are taught and treated, as well as show testimony/images of work from successful students.

The style of the brochure is very aged and worn-looking, with warm colors like red, orange and gold. The headlines and sub-heads use a larger, gothic-inspired font to make them stand out from the rest of the text on the page; the larger size of the letters makes them easier to read than if they were any smaller. The body text uses a common serif font, which makes the bulk of the text easier to read than if it were written in the gothic font.

The artwork is dynamic and interesting, even as a background to the page. The images used to display previous students’ work is also of good output. However, I feel like the students’ images look awkward when compared to the rest of the page—the feeling of antiquity and roughness is shattered with a picture of a modern day machine, as well as crisp and clear imagery. I feel like perhaps there could have been some other way to incorporate the images or make them feel more rough—like make the outline a ripped page instead of a simple black line. But I really liked the piece because it reminded me of the illuminated manuscripts we have been studying, with the parchment/rough texture and warm colorings (red and gold especially), as well as the use of black lettering with bigger letters beginning each paragraph.

Friday, February 13, 2009

After Class 2/13

1. Name of graphic style (or topic) studied this session:

Today we talked about illuminated manuscripts as well as printing’s beginnings in Europe.

2. Describe specific qualities of this style (or if it’s a topic-highlights of that topic) that will help you identify it in the future.

Celtic manuscripts were very ornate and decorated; full pages of decoration were “carpet pages.” Romanesque/Gothic design, like the Douce Apocalypse, used the dense littera moderna (textura) type. Late Medieval texts, like the Book of Hours created by the Limbourg brothers, were also very ornate and used different colors of type like red to call out important things.

Gutenberg was the first to make movable type in Europe and did so by perfecting the metal alloy for the type molds. He first printed the 42-line Bible. Playing cards were the first pieces printed that all classes could obtain.

3. What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today?

It was useful to see the transformation of the different illuminated texts; in a way, you can look to your own designs and see an evolution of design that reflect who you were/how you thought at the moment, just as it seems in illuminated texts.

4. Question:

Did Gutenberg share his special alloy mix with others right away to help movable type along, or did others have to figure it out on their own?

Today we talked about illuminated manuscripts as well as printing’s beginnings in Europe.

2. Describe specific qualities of this style (or if it’s a topic-highlights of that topic) that will help you identify it in the future.

Celtic manuscripts were very ornate and decorated; full pages of decoration were “carpet pages.” Romanesque/Gothic design, like the Douce Apocalypse, used the dense littera moderna (textura) type. Late Medieval texts, like the Book of Hours created by the Limbourg brothers, were also very ornate and used different colors of type like red to call out important things.

Gutenberg was the first to make movable type in Europe and did so by perfecting the metal alloy for the type molds. He first printed the 42-line Bible. Playing cards were the first pieces printed that all classes could obtain.

3. What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today?

It was useful to see the transformation of the different illuminated texts; in a way, you can look to your own designs and see an evolution of design that reflect who you were/how you thought at the moment, just as it seems in illuminated texts.

4. Question:

Did Gutenberg share his special alloy mix with others right away to help movable type along, or did others have to figure it out on their own?

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Chapter 5

Chapter 5: Printing Comes to Europe

Typography, or the “printing with independent, movable, and reusable bits of metal or wood, each of which has a raised letterform on one face,” helped knowledge and literacy to quickly spread throughout the world once it was invented. Europeans first used woodblock printing, making playing cards a very popular item among rich and poor alike, as well as proliferating devotional and religious matter. When paper was finally introduced to Europe, the want for books soared. In 1450, Gutenberg was finally able to put a system together and print a typographical book. The typeface had to be precisely made out of metal casts so that all letters would be the same sizes and align evenly, as well as last for thousands of imprints. Gutenberg saw many of the first, most popular texts printed from his presses, including the first typographic Bibles; and printers Fust and brought about two-part metal blocks that could print two colors, just one of their many achievements. Copperplate engraving as a means of printing was popular too, and it is thought that Gutenberg most likely had a hand in this as well.

What I thought so interesting about this chapter was that movable type came into being long before I thought it had, in 1450—over 500 years ago. I thought it would come to be much later in history.

Was Gutenberg influenced by the Asian’s discovery of movable type, or did he innovate this for the Europeans on his own with no influence from the outside?

Typography, or the “printing with independent, movable, and reusable bits of metal or wood, each of which has a raised letterform on one face,” helped knowledge and literacy to quickly spread throughout the world once it was invented. Europeans first used woodblock printing, making playing cards a very popular item among rich and poor alike, as well as proliferating devotional and religious matter. When paper was finally introduced to Europe, the want for books soared. In 1450, Gutenberg was finally able to put a system together and print a typographical book. The typeface had to be precisely made out of metal casts so that all letters would be the same sizes and align evenly, as well as last for thousands of imprints. Gutenberg saw many of the first, most popular texts printed from his presses, including the first typographic Bibles; and printers Fust and brought about two-part metal blocks that could print two colors, just one of their many achievements. Copperplate engraving as a means of printing was popular too, and it is thought that Gutenberg most likely had a hand in this as well.

What I thought so interesting about this chapter was that movable type came into being long before I thought it had, in 1450—over 500 years ago. I thought it would come to be much later in history.

Was Gutenberg influenced by the Asian’s discovery of movable type, or did he innovate this for the Europeans on his own with no influence from the outside?

After Class 2/11

1. Name of graphic style (or topic) studied this session:

We briefly talked about the Asian influence of language and typography.

2. Describe specific qualities of this style (or if it’s a topic-highlights of that topic) that will help you identify it in the future.

Chinese started out with bone-and-shell script, reading the cracks in bones formed from a hot poker. It then moved to writing on bronze, often in vessels like pots, etc. Regular style calligraphy then came into use and has been ever since; the strokes of the calligrapher can represent spiritual and emotional states of the writers.

3. What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today?

I thought it was very interesting that the calligraphic strokes can represent emotional and spiritual feelings of a writer; in simplistic designs, I think it would be very useful to keep this in mind as it would perhaps give a deeper subconscious feeling to pieces of design I work on.

I also learned not to try to learn Chinese—over 40,000 letterforms…yikes.

4. Question:

What made diviners shift from only disentangling prophecies out of cracks in bone to turning those cracks into their own forms of thought in written form?

We briefly talked about the Asian influence of language and typography.

2. Describe specific qualities of this style (or if it’s a topic-highlights of that topic) that will help you identify it in the future.

Chinese started out with bone-and-shell script, reading the cracks in bones formed from a hot poker. It then moved to writing on bronze, often in vessels like pots, etc. Regular style calligraphy then came into use and has been ever since; the strokes of the calligrapher can represent spiritual and emotional states of the writers.

3. What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today?

I thought it was very interesting that the calligraphic strokes can represent emotional and spiritual feelings of a writer; in simplistic designs, I think it would be very useful to keep this in mind as it would perhaps give a deeper subconscious feeling to pieces of design I work on.

I also learned not to try to learn Chinese—over 40,000 letterforms…yikes.

4. Question:

What made diviners shift from only disentangling prophecies out of cracks in bone to turning those cracks into their own forms of thought in written form?

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Chapters 3 & 4

Chapter 3: The Asian Contribution

The Chinese civilization’s origin is steeped in mystery, but we do know that their language system has always been based on pictorial representations of words rather than an alphabet of letters, logograms presumably first written in 1800 BC by Tsang Chieh. The earliest writings were called chiaku-wen (“bone-and-shell” script) from 1800-1200 BC; the chin-wen (“bronze” script) followed. Emperor Shih Huang Ti united all written Chinese forms in the 3rd century BCE. Finally, chen-shu (“regular” style) script was created and has been used for almost 2000 years. The ink figures can vary by each writer; every stroke of every letter is a form of art to the Chinese. In 105 AD, Ts’ai Lun is said to have probably been the man to have invented paper; another breakthrough by the Chinese was that of printing, beginning with the carved reliefs that Chinese would make for seals. Chinese created many manuscripts, and even invented the first playing cards.

What interested me the most about the Chinese culture is that they were the civilization that created movable type; but that they had over 40,000 different logograms to move around instead of the normal 26 letters that we have today.

I wonder, would it be worth their time to print out documents with movable type (1000 years ago) if one had to find one symbol of type amongst thousands, instead of just one letter out of 26?

\\\

Chapter 4: Illuminated Manuscripts

Illuminated manuscripts were popular beginning in the late Roman Empire until through the Renaissance time period. Classical style manuscripts were layouts of text with small, crisp illustrations; there was often one column of text and illustrations were framed with bright strokes of color. Celtic manuscripts were more abstract and complex; vivid colors fill the pages, as do woven intricate textures and patterns; full-page illustrations were used, as well as large initials on opening pages. After time, spaces were left between words to help readers, and half-uncials began to be used too. During Charlemagne’s reign in the late 700s-early 800s, he standardized page layout, writing style and decoration. Caroline miniscules was the accepted writing style; pictures were often given frames to give an illusion of depth. Spanish manuscripts started to adopt Islamic motifs like flat, broad shapes of color decorative and intricate frames, and intense color. Romanesque/Gothic manuscripts saw a revival of religious themes and used intense Textura (black, strong) type. Judaic manuscripts, though rare, are remarkable examples of painstaking illustration and calligraphy. Islamic manuscripts became increasingly ornate with geometric and arabesque designs, little blank space, but rarely any figurative illustration. Late medieval manuscripts were the most ornate and beautiful of all; they were daily devotionals of prayer and their gold-leafed, jeweled, richly illustrated beauty represented the esteem the book’s owner held for God.

The difference in each region's design and reverance of the illuminated manuscript was the most interesting part of the chapter to keep tabs on. It showed a lot about each culture and the importance they felt for scribes and literature, for the proliferation of knowledge, culture and religion. It also showed the extravagance that some cultures would go to, sometimes overly extreme, that perhaps gives away insecurity that a culture felt under the scrutiny of divine eyes.

What I question is were all important manuscripts written in these styles, or was it always just manuscripts that concerned religion?

The Chinese civilization’s origin is steeped in mystery, but we do know that their language system has always been based on pictorial representations of words rather than an alphabet of letters, logograms presumably first written in 1800 BC by Tsang Chieh. The earliest writings were called chiaku-wen (“bone-and-shell” script) from 1800-1200 BC; the chin-wen (“bronze” script) followed. Emperor Shih Huang Ti united all written Chinese forms in the 3rd century BCE. Finally, chen-shu (“regular” style) script was created and has been used for almost 2000 years. The ink figures can vary by each writer; every stroke of every letter is a form of art to the Chinese. In 105 AD, Ts’ai Lun is said to have probably been the man to have invented paper; another breakthrough by the Chinese was that of printing, beginning with the carved reliefs that Chinese would make for seals. Chinese created many manuscripts, and even invented the first playing cards.

What interested me the most about the Chinese culture is that they were the civilization that created movable type; but that they had over 40,000 different logograms to move around instead of the normal 26 letters that we have today.

I wonder, would it be worth their time to print out documents with movable type (1000 years ago) if one had to find one symbol of type amongst thousands, instead of just one letter out of 26?

\\\

Chapter 4: Illuminated Manuscripts

Illuminated manuscripts were popular beginning in the late Roman Empire until through the Renaissance time period. Classical style manuscripts were layouts of text with small, crisp illustrations; there was often one column of text and illustrations were framed with bright strokes of color. Celtic manuscripts were more abstract and complex; vivid colors fill the pages, as do woven intricate textures and patterns; full-page illustrations were used, as well as large initials on opening pages. After time, spaces were left between words to help readers, and half-uncials began to be used too. During Charlemagne’s reign in the late 700s-early 800s, he standardized page layout, writing style and decoration. Caroline miniscules was the accepted writing style; pictures were often given frames to give an illusion of depth. Spanish manuscripts started to adopt Islamic motifs like flat, broad shapes of color decorative and intricate frames, and intense color. Romanesque/Gothic manuscripts saw a revival of religious themes and used intense Textura (black, strong) type. Judaic manuscripts, though rare, are remarkable examples of painstaking illustration and calligraphy. Islamic manuscripts became increasingly ornate with geometric and arabesque designs, little blank space, but rarely any figurative illustration. Late medieval manuscripts were the most ornate and beautiful of all; they were daily devotionals of prayer and their gold-leafed, jeweled, richly illustrated beauty represented the esteem the book’s owner held for God.

The difference in each region's design and reverance of the illuminated manuscript was the most interesting part of the chapter to keep tabs on. It showed a lot about each culture and the importance they felt for scribes and literature, for the proliferation of knowledge, culture and religion. It also showed the extravagance that some cultures would go to, sometimes overly extreme, that perhaps gives away insecurity that a culture felt under the scrutiny of divine eyes.

What I question is were all important manuscripts written in these styles, or was it always just manuscripts that concerned religion?

After Class 2/9

Name of graphic style (or topic) studied this session:

Alphabets

Describe specific qualities of this style (or if it’s a topic, highlights of that topic) that will help you identify it in the future:

The Greek alphabet was a major achievement because it was the first to have vowels and be more phonetic; aesthetically, it was more geometric, symmetrical and organized. The Roman Empire, at its height in 100 CE, was also a major influence as they erected triumphal arches that introduced serifs and ligatures. Ireland had its hand in forming uncials (square, rustic lettering) as well as half-uncials, which are like our lower-case letters we have today. Finally, Charlemagne’s rule in 768 CE dictated that Caroline Minuscule/Carolingian hand become the standard of writing to his people.

What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today?

I enjoyed learning about how language is finally starting to look like that of our own language; it is interesting to see how much it had evolved at first (since ancient times) yet how little it seems to have evolved since Roman times as well.

Question:

What led the Celtic peoples to create half-uncials?

Alphabets

Describe specific qualities of this style (or if it’s a topic, highlights of that topic) that will help you identify it in the future:

The Greek alphabet was a major achievement because it was the first to have vowels and be more phonetic; aesthetically, it was more geometric, symmetrical and organized. The Roman Empire, at its height in 100 CE, was also a major influence as they erected triumphal arches that introduced serifs and ligatures. Ireland had its hand in forming uncials (square, rustic lettering) as well as half-uncials, which are like our lower-case letters we have today. Finally, Charlemagne’s rule in 768 CE dictated that Caroline Minuscule/Carolingian hand become the standard of writing to his people.

What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today?

I enjoyed learning about how language is finally starting to look like that of our own language; it is interesting to see how much it had evolved at first (since ancient times) yet how little it seems to have evolved since Roman times as well.

Question:

What led the Celtic peoples to create half-uncials?

Monday, February 9, 2009

Reading for Class 2/9

Chapter Two: Alphabets

Early forms of written language were comprised of pictographs for whole words instead of written forms for individual letters; Crete pictographs are speculated to be the origin of the modern-day alphabet. The North Semitic people, however, are believed to be the creators of the first alphabet. Around 1500 B.C., Sinaitic script was developed by Egyptian workers, followed shortly by Ras Shamra, a "true Semitic alphabetical script" minus any vowels. The oldest forms of Hebrew were found from 1000 B.C. Arabic writing, developed before 500 A.D., added six vowels to the end of the Semitic alphabet, spreading to become the most widely used alphabet today. Greece's alphabet developed earlier than the 8th century B.C., and the country's great success and influence spread the language through many lands and influencing the letterforms that we use today derived from the Latin alphabet.

I found the Phaistos Disc to be an interesting piece of the chapter that stuck out to me. Probably because I was just visiting Crete in Greece, and got to see the disc in person, it especially connected with me. It is also a great mystery that people will speculate about for a long time (perhaps forever), but the beauty and design of the disc is something that will continue to be admired as well. It is an example of moveable type, and it is astonishing to me that thousands of years ago these people were able to come up with the concept of type like that.

The question I ponder as I read this chapter is, how different would things be if we’d all used the same alphabet—would we have advanced to something far beyond our intelligence, or would only using one alphabet form have stifled our minds?

Early forms of written language were comprised of pictographs for whole words instead of written forms for individual letters; Crete pictographs are speculated to be the origin of the modern-day alphabet. The North Semitic people, however, are believed to be the creators of the first alphabet. Around 1500 B.C., Sinaitic script was developed by Egyptian workers, followed shortly by Ras Shamra, a "true Semitic alphabetical script" minus any vowels. The oldest forms of Hebrew were found from 1000 B.C. Arabic writing, developed before 500 A.D., added six vowels to the end of the Semitic alphabet, spreading to become the most widely used alphabet today. Greece's alphabet developed earlier than the 8th century B.C., and the country's great success and influence spread the language through many lands and influencing the letterforms that we use today derived from the Latin alphabet.

I found the Phaistos Disc to be an interesting piece of the chapter that stuck out to me. Probably because I was just visiting Crete in Greece, and got to see the disc in person, it especially connected with me. It is also a great mystery that people will speculate about for a long time (perhaps forever), but the beauty and design of the disc is something that will continue to be admired as well. It is an example of moveable type, and it is astonishing to me that thousands of years ago these people were able to come up with the concept of type like that.

The question I ponder as I read this chapter is, how different would things be if we’d all used the same alphabet—would we have advanced to something far beyond our intelligence, or would only using one alphabet form have stifled our minds?

Sunday, February 8, 2009

Weekly Image

Describe what it is: This is an ad for Volkswagen’s Golf GTI car.

Describe its function: The ad is showing pictographs of people/vehicles along a circular progression, which simulates the idea of a speedometer of a car. This shows the progression that the car’s speed takes, starting out with the slowest speed (which is akin to the walk of a police officer) and going up to as fast as a helicopter. This is supposed to show the range of pace the car can take, ultimately out-speeding a car to reach speeds of a helicopter (yeah, okay).

Describe where you saw it: I saw it on the Ads of the World advertising archive: http://adsoftheworld.com/media/outdoor/volkswagen_golf_gti_police

Discuss the style of the design & typography: The design is pretty straightforward; the pictographs are easy to recognize for what they represent, like a police officer standing, then running, then sprinting, etc. There is barely any typography, which allows the images to do all the “talking” for the ad. The only typography is the km/h, which simply helps to get across the idea of a speedometer, though I don’t think that was even needed in the ad to get that point across.

Discuss the quality of the artwork: The artwork is very detailed for such small pictographs, but that helps to get each individual picture’s specific idea across.

Discuss what attracted you to the piece: The movement of the piece attracted me at first, I think, because of the circular motion that moves your eye around the piece and back to the beginning of the speedometer, allowing you to take it in as a whole at first. Then on second look, all the components come together overall and you see it as a speed dial. Also, I like the way the artwork is rendered, almost like the pictures are hand drawings. It gives the piece an older feel, like it is around the comic book era, when car races and speed (Speed Racer) were popular. I like that feeling it gives to the ad.

Describe how it relates to what we have discussed or read: This relates to the idea of simple pictographs portraying ideas like the ancient styles of handwriting. The pictographs/ideographs that are used here show pictures/give the idea of people running, driving, chasing, etc. This is a good example of how simpler images can come together to create a bigger thematic idea.

Saturday, February 7, 2009

After Class 2/6

1. Name of graphic style (or topic) studied this session:

Ancient writing styles - pictographs, ideographs, cuneiform, hieroglyphics

2. Describe specific qualities of this style (or if it’s a topic-highlights of that topic) that will help you identify it in the future.

Ancient writing styles were first made of pictographs and ideographs that represented a word or idea. For example, the word "fish" was a picture of a fish. Cave paintings in 8000 BC used this type of writing style. Hieroglyphs are the most recognizable forms of ancient writing. Cuneiform followed that in 3200 BC, a style of writing made with wedge-shaped strokes.

3. What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today?

I never thought of trying to use my own pictographs or ancient writing-inspired type/pictures in my designs. But it would be an interesting approach to take in an appropriate context to try to push myself to fit an idea or word in one image.

4. Question: How did some languages communicate without letters/words (like Phoenicians, who had no vowels)?

Ancient writing styles - pictographs, ideographs, cuneiform, hieroglyphics

2. Describe specific qualities of this style (or if it’s a topic-highlights of that topic) that will help you identify it in the future.

Ancient writing styles were first made of pictographs and ideographs that represented a word or idea. For example, the word "fish" was a picture of a fish. Cave paintings in 8000 BC used this type of writing style. Hieroglyphs are the most recognizable forms of ancient writing. Cuneiform followed that in 3200 BC, a style of writing made with wedge-shaped strokes.

3. What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today?

I never thought of trying to use my own pictographs or ancient writing-inspired type/pictures in my designs. But it would be an interesting approach to take in an appropriate context to try to push myself to fit an idea or word in one image.

4. Question: How did some languages communicate without letters/words (like Phoenicians, who had no vowels)?

Thursday, February 5, 2009

Reading for 2/6: The Invention of Writing

When Homo sapiens surfaced in history is unknown, but the earliest forms of human markings were found in Africa dating from over 200,000 years ago as cave paintings. Geometric symbols, man figures and animal symbols were used; later, these symbols were abbreviated to the bare minimum, mostly using just simple lines. As ancient cultures evolved and records had to be taken of crops, taxes, and much more, pictographic drawings and numerals were developed and used. Cuneiform writing (using a wedge-shaped tool) made writing faster and easier, and scribes began to expand the meaning of one pictograph into several ideas. Eventually, written symbols became signatures for people, and cylinder seals engraved with pictures were used on clay to indicate the writer’s or artisan’s identity. The abstract symbols, like the hieroglyphs found on the Rosetta Stone from 197-196 B.C., stumped scholars for ages until Jean-Francois Champollion made a breakthrough in 1822. The Egyptians also made skilled use of papyrus, which gave rise to many manuscripts that we hold in historical reverence today, such as the Book of the Dead. By using our knowledge of hieroglyphs and their meaning, as well as the many clay tablets and papyrus forms of writing, we have been able to unlock the secrets of ancient nations that were long silent legends.

In the reading, I found Jean-Francois Champollion to be the most interesting figure. It took about 2000 years for anyone to break through the hieroglyphs' meanings, and that he was the man to do it automatically catches my attention. I don’t know how long he had to study the Rosetta Stone to find the names “Ptolemy” and “Cleopatra” but I can only imagine it took unnumbered hours of frustrating, fruitless analysis. Not only did his discoveries help to uncover information about the Egyptians, but it also gave rise to information about the cultures and people that preceded the Egyptians, as well as probably shed some light onto what happened following the Egyptians reign.

Although many languages may use the same letterforms, Chinese and English symbols greatly differ, as well as Greek, Hebrew, Arabic and more. One question I still have is what path written language took to form the different symbols of different languages.

In the reading, I found Jean-Francois Champollion to be the most interesting figure. It took about 2000 years for anyone to break through the hieroglyphs' meanings, and that he was the man to do it automatically catches my attention. I don’t know how long he had to study the Rosetta Stone to find the names “Ptolemy” and “Cleopatra” but I can only imagine it took unnumbered hours of frustrating, fruitless analysis. Not only did his discoveries help to uncover information about the Egyptians, but it also gave rise to information about the cultures and people that preceded the Egyptians, as well as probably shed some light onto what happened following the Egyptians reign.

Although many languages may use the same letterforms, Chinese and English symbols greatly differ, as well as Greek, Hebrew, Arabic and more. One question I still have is what path written language took to form the different symbols of different languages.

Wednesday, February 4, 2009

2/4 After Class

1. Name of topic we looked at this session, dealing with history:

Ancient Cavemen Communication - Heiroglyphics

3. What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today (from class Wednesday)?

How difficult it is to convey certain ideas or words without using the alphabet/symbols, and how we can find just the right graphics to help convey ideas. Even just trying to convey the idea of "there were" had me at a loss, as did trying to convey colors without using the actual color.

4. State at least one question you have after the class.

How many heiroglyphs did the cavemen have so that they were able to understand each other and communicate?

Ancient Cavemen Communication - Heiroglyphics

3. What is the most useful or meaningful thing you learned today (from class Wednesday)?

How difficult it is to convey certain ideas or words without using the alphabet/symbols, and how we can find just the right graphics to help convey ideas. Even just trying to convey the idea of "there were" had me at a loss, as did trying to convey colors without using the actual color.

4. State at least one question you have after the class.

How many heiroglyphs did the cavemen have so that they were able to understand each other and communicate?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)